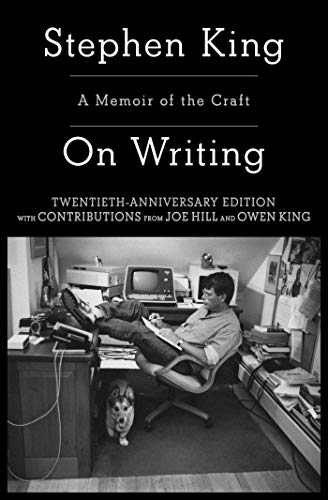

On Writing

Although I have never read any of Stephen King’s novels, I have heard about the man enough to respect him as a writer. So when I found out that he wrote a book on writing, I immediately bought a copy and read it over the weekend.

This book offers many practical ideas that will make you a better writer. In addition, many of King’s suggestions to become a better writer also apply to becoming a better programmer. Just replace writing with programming, and you are good to go.

Put another way, to write is human, to edit is devine.

What follows is an attempt to put down, briefly and simply, how I came to the craft, what I know about it now, and how it’s done. It’s about my day job; it’s about the language.

At some point I began to write my own stories. Imitation preceded creation; I would copy Combat Casey comics word for word in my Blue Horse tablet, sometimes adding my own descriptions where they seemed appropriate.

When I got the rejection slip from AHMM, I pounded a nail into the wall above the Webcor, wrote “Happy Stamps” on the rejection slip, and poked it onto the nail.

By the time I was fourteen (and shaving twice a week whether I needed to or not) the nail in my wall would no longer support the weight of the rejection slips impaled upon it. I replaced the nail with a spike and went on writing. By the time I was sixteen I’d begun to get rejection slips with handwritten notes a little more encouraging than the advice to stop using staples and start using paperclips.

“When you write a story, you’re telling yourself the story,” he said. “When you rewrite, your main job is taking out all the things that are not the story.”

I was afraid that I wouldn’t be able to work anymore if I quit drinking and drugging, but I decided (again, so far as I was able to decide anything in my distraught and depressed state of mind) that I would trade writing for staying married and watching the kids grow up. If it came to that.

It didn’t, of course.

The idea that creative endeavor and mind-altering substances are entwined is one of the great pop-intellectual myths of our time.

Substance-abusing writers are just substance abusers—common garden-variety drunks and druggies, in other words. Any claims that the drugs and alcohol are necessary to dull a finer sensibility are just the usual self-serving bullshit.

It starts with this: put your desk in the corner, and every time you sit down there to write, remind yourself why it isn’t in the middle of the room. Life isn’t a support-system for art. It’s the other way around.

Writing Is Telepathy

Telepathy, of course. It’s amusing when you stop to think about it—for years people have argued about whether or not such a thing exists, folks like J. B. Rhine have busted their brains trying to create a valid testing process to isolate it, and all the time it’s been right there, lying out in the open like Mr. Poe’s Purloined Letter. All the arts depend upon telepathy to some degree, but I believe that writing offers the purest distillation.

This is what we’re looking at, and we all see it. I didn’t tell you. You didn’t ask me. I never opened my mouth and you never opened yours. We’re not even in the same year together, let alone the same room . . . . except we are together. We’re close. We’re having a meeting of the minds.

Writing Tools

I want to suggest that to write to your best abilities, it behooves you to construct your own toolbox and then build up enough muscle so you can carry it with you. Then, instead of looking at a hard job and getting discouraged, you will perhaps seize the correct tool and get immediately to work.

Vocabulary

Put your vocabulary on the top shelf of your toolbox, and don’t make any conscious effort to improve it. (You’ll be doing that as you read, of course . . . . but that comes later.) One of the really bad things you can do to your writing is to dress up the vocabulary, looking for long words because you’re maybe a little bit ashamed of your short ones.

I’m not trying to get you to talk dirty, only plain and direct. Remember that the basic rule of vocabulary is use the first word that comes to your mind, if it is appropriate and colorful.

You might also notice how much simpler the thought is to understand when it’s broken up into two thoughts. This makes matters easier for the reader, and the reader must always be your main concern; without Constant Reader, you are just a voice quacking in the void.

The adverb is not your friend.

Paragraphs

The paragraph, not the sentence, is the basic unit of writing—the place where coherence begins and words stand a chance of becoming more than mere words. You must learn to use it well if you are to write well. What this means is lots of practice; you have to learn the beat.

Easy books contain lots of short paragraphs—including dialogue paragraphs which may only be a word or two long—and lots of white space.

In expository prose, paragraphs can (and should) be neat and utilitarian. The ideal expository graf contains a topic sentence followed by others which explain or amplify the first.

Topic-sentence-followed-by-support-and-description insists that the writer organize his/her thoughts, and it also provides good insurance against wandering away from the topic. Wandering isn’t a big deal in an informal essay, is practically de rigueur, as a matter of fact—but it’s a very bad habit to get into when working on more serious subjects in a more formal manner. Writing is refined thinking.

The more fiction you read and write, the more you’ll find your paragraphs forming on their own. And that’s what you want. When composing it’s best not to think too much about where paragraphs begin and end; the trick is to let nature take its course. If you don’t like it later on, fix it then. That’s what rewrite is all about.

You will build a paragraph at a time, constructing these of your vocabulary and your knowledge of grammar and basic style. As long as you stay level-on-the-level and shave even every door, you can build whatever you like—whole mansions, if you have the energy.

At its most basic we are only discussing a learned skill, but do we not agree that sometimes the most basic skills can create things far beyond our expectations? We are talking about tools and carpentry, about words and style . . . . but as we move along, you’d do well to remember that we are also talking about magic.

On Writing

I am approaching the heart of this book with two theses, both simple.

- Good writing consists of mastering the fundamentals (vocabulary, grammar, the elements of style) and then filling the third level of your toolbox with the right instruments.

- While it is impossible to make a competent writer out of a bad writer, and while it is equally impossible to make a great writer out of a good one, it is possible, with lots of hard work, dedication, and timely help, to make a good writer out of a merely competent one.

What follows is everything I know about how to write good fiction. I’ll be as brief as possible, because your time is valuable and so is mine, and we both understand that the hours we spend talking about writing is time we don’t spend actually doing it.

if you don’t want to work your ass off, you have no business trying to write well—settle back into competency and be grateful you have even that much to fall back on.

There is a muse, but he’s not going to come fluttering down into your writing room and scatter creative fairy-dust all over your typewriter or computer station. He lives in the ground. He’s a basement guy. You have to descend to his level, and once you get down there you have to furnish an apartment for him to live in. You have to do all the grunt labor, in other words, while the muse sits and smokes cigars and admires his bowling trophies and pretends to ignore you.

Do you think this is fair? I think it’s fair. He may not be much to look at, that muse-guy, and he may not be much of a conversationalist (what I get out of mine is mostly surly grunts, unless he’s on duty), but he’s got the inspiration. It’s right that you should do all the work and burn all the midnight oil, because the guy with the cigar and the little wings has got a bag of magic. There’s stuff in there that can change your life.

Believe me, I know.

If you want to be a writer, you must do two things above all others: read a lot and write a lot. There’s no way around these two things that I’m aware of, no shortcut.

I’m a slow reader, but I usually get through seventy or eighty books a year, mostly fiction. I don’t read in order to study the craft; I read because I like to read. It’s what I do at night, kicked back in my blue chair. Similarly, I don’t read fiction to study the art of fiction, but simply simply because I like stories. Yet there is a learning process going on. Every book you pick up has its own lesson or lessons, and quite often the bad books have more to teach than the good ones.

What could be more encouraging to the struggling writer than to realize his/her work is unquestionably better than that of someone who actually got paid for his/her stuff?

One learns most clearly what not to do by reading bad prose.

Good writing, on the other hand, teaches the learning writer about style, graceful narration, plot development, the creation of believable characters, and truth-telling. It can also serve as a spur, goading the writer to work harder and aim higher. Being swept away by a combination of great story and great writing—of being flattened, in fact—is part of every writer’s necessary formation. You cannot hope to sweep someone else away by the force of your writing until it has been done to you.

So we read to experience the mediocre and the outright rotten; such experience helps us to recognize those things when they begin to creep into our own work, and to steer clear of them. We also read in order to measure ourselves against the good and the great, to get a sense of all that can be done. And we read in order to experience different styles.

I enjoyed reading a wide range of authors. When I started writing, all these styles merged, creating a kind of hilarious stew. This sort of stylistic blending is a necessary part of developing one’s own style, but it doesn’t occur in a vacuum. You have to read widely, constantly refining (and redefining) your own work as you do so.

If you don’t have time to read, you don’t have the time (or the tools) to write. Simple as that.

Reading is the creative center of a writer’s life. I take a book with me everywhere I go, and find there are all sorts of opportunities to dip in. The trick is to teach yourself to read in small sips as well as in long swallows.

Reading at meals is considered rude in polite society, but if you expect to succeed as a writer, rudeness should be the second-to-least of your concerns. The least of all should be polite society and what it expects.

The real importance of reading is that it creates an ease and intimacy with the process of writing; one comes to the country of the writer with one’s papers and identification pretty much in order.

Constant reading will pull you into a place (a mind-set, if you like the phrase) where you can write eagerly and without self-consciousness. It also offers you a constantly growing knowledge of what has been done and what hasn’t, what is trite and what is fresh, what works and what just lies there dying (or dead) on the page.

The more you read, the less apt you are to make a fool of yourself with your pen or word processor.

Routine

My own schedule is pretty clear-cut. Mornings belong to whatever is new—the current composition. Afternoons are for naps and letters. Evenings are for reading, family, Red Sox games on TV, and any revisions that just cannot wait. Basically, mornings are my prime writing time.

Once I start work on a project, I don’t stop and I don’t slow down unless I absolutely have to. If I don’t write every day, the characters begin to stale off in my mind—they begin to seem like characters instead of real people.

I like to get ten pages a day, which amounts to 2,000 words. That’s 180,000 words over a three-month span, a goodish length for a book—something in which the reader can get happily lost, if the tale is done well and stays fresh. only under dire circumstances do I allow myself to shut down before I get my 2,000 words.

The biggest aid to regular (Trollopian?) production is working in a serene atmosphere.

It’s difficult for even the most naturally productive writer to work in an environment where alarms and excursions are the rule rather than the exception. When I’m asked for “the secret of my success” (an absurd idea, that, but impossible to get away from), I sometimes say there are two: I stayed physically healthy (at least until a van knocked me down by the side of the road in the summer of 1999), and I stayed married.

It’s a good answer because it makes the question go away, and because there is an element of truth in it. The combination of a healthy body and a stable relationship with a self-reliant woman who takes zero shit from me or anyone else has made the continuity of my working life possible. And I believe the converse is also true: that my writing and the pleasure I take in it has contributed to the stability of my health and my home life.

Most of us do our best in a place of our own. Until you get one, you’ll find your new resolution to write a lot hard to take seriously. The space can be humble (probably should be, as I think I have already suggested), and it really needs only one thing: a door which you are willing to shut. The closed door is your way of telling the world and yourself that you mean business; you have made a serious commitment to write and intend to walk the walk as well as talk the talk.

By the time you step into your new writing space and close the door, you should have settled on a daily writing goal. As with physical exercise, it would be best to set this goal low at first, to avoid discouragement. I suggest a thousand words a day, and because I’m feeling magnanimous, I’ll also suggest that you can take one day a week off, at least to begin with. No more; you’ll lose the urgency and immediacy of your story if you do. With that goal set, resolve to yourself that the door stays closed until that goal is met. Get busy putting those thousand words on paper or computer.

For any writer, but for the beginning writer in particular, it’s wise to eliminate every possible distraction. If you continue to write, you will begin to filter out these distractions naturally, but at the start it’s best to try and take care of them before you write. No telephone, no email, no television, videogame, nothing.

Like your bedroom, your writing room should be private, a place where you go to dream. Your schedule—in at about the same time every day, out when your thousand words are on paper or disk—exists in order to habituate yourself, to make yourself ready to dream just as you make yourself ready to sleep by going to bed at roughly the same time each night and following the same ritual as you go. In both writing and sleeping, we learn to be physically still at the same time we are encouraging our minds to unlock from the humdrum rational thinking of our daytime lives. And as your mind and body grow accustomed to a certain amount of sleep each night—six hours, seven, maybe the recommended eight—so can you train your waking mind to sleep creatively and work out the vividly imagined waking dreams which are successful works of fiction.

But you need the room, you need the door, and you need the determination to shut the door. You need a concrete goal, as well.

The longer you keep to these basics, the easier the act of writing will become. Don’t wait for the muse. Your job is to make sure the muse knows where you’re going to be every day from nine ‘til noon or seven ‘til three. If he does know, I assure you that sooner or later he’ll start showing up, chomping his cigar and making his magic.

Now comes the big question: What are you going to write about? And the equally big answer: Anything you damn well want. Anything at all . . . . as long as you tell the truth.

In terms of genre, it’s probably fair to assume that you will begin by writing what you love to read. What would be very wrong, I think, is to turn away from what you know and like (or love, the way I loved those old ECs and black-and-white horror flicks) in favor of things you believe will impress your friends, relatives, and writing-circle colleagues.

Stylistic imitation is one thing, a perfectly honorable way to get started as a writer (and impossible to avoid, really; some sort of imitation marks each new stage of a writer’s development),

Write what you like, then imbue it with life and make it unique by blending in your own personal knowledge of life, friendship, relationships, sex, and work. Especially work. People love to read about work. God knows why, but they do. If you’re a plumber who enjoys science fiction, you might well consider a novel about a plumber aboard a starship or on an alien planet.

How to Write

In my view, stories and novels consist of three parts:

- Narration: moves the story from point A to point B and finally to point Z

- Description: creates a sensory reality for the reader

- Dialogue: brings characters to life through their speech

Good description is a learned skill, one of the prime reasons why you cannot succeed unless you read a lot and write a lot. Description begins with visualization of what it is you want the reader to experience. It ends with your translating what you see in your mind into words on the page. Good description usually consists of a few well-chosen details that will stand for everything else. In most cases, these details will be the first ones that come to mind.

The key to good description begins with clear seeing and ends with clear writing, the kind of writing that employs fresh images and simple vocabulary. As with all other aspects of the narrative art, you will improve with practice, but practice will never make you perfect. Why should it? What fun would that be? And the harder you try to be clear and simple, the more you will learn about the complexity of our American dialect. It be slippery, precious; aye, it be very slippery, indeed. Practice the art, always reminding yourself that your job is to say what you see, and then to get on with your story.

One of the cardinal rules of good fiction is never tell us a thing if you can show us. Talk is sneaky: what people say often conveys their character to others in ways of which they—the speakers—are completely unaware.

Everything I’ve said about dialogue applies to building characters in fiction. The job boils down to two things:

- paying attention to how the real people around you behave, and then

- telling the truth about what you see.

Core ideas: practice is invaluable (and should feel good, really not like practice at all) and that honesty is indispensable. Skills in description, dialogue, and character development all boil down to seeing or hearing clearly and then transcribing what you see or hear with equal clarity (and without using a lot of tiresome, unnecessary adverbs).

No matter how you do it, there comes a point when you must judge what you’ve written and how well you wrote it. I don’t believe a story or a novel should be allowed outside the door of your study or writing room unless you feel confident that it’s reasonably reader-friendly. You can’t please all of the readers all of the time; you can’t please even some of the readers all of the time, but you really ought to try to please at least some of the readers some of the time.

Revising the Work

In actual practice, rewriting varies greatly from writer to writer. If you’re a beginner, let me urge that you take your story through at least two drafts; the one you do with the study door closed and the one you do with it open.

With the door shut, downloading what’s in my head directly to the page, I write as fast as I can and still remain comfortable. Writing fiction, especially a long work of fiction, can be a difficult, lonely job; it’s like crossing the Atlantic Ocean in a bathtub. There’s plenty of opportunity for self-doubt. If I write rapidly, putting down my story exactly as it comes into my mind, only looking back to check the names of my characters and the relevant parts of their back stories, I find that I can keep up with my original enthusiasm and at the same time outrun the self-doubt that’s always waiting to settle in.

After finishing the first draft, it’s time to rest. You’ve done a lot of work and you need a period of time (how much or how little depends on the individual writer) to rest. Your mind and imagination—two things which are related, but not really the same—have to recycle themselves, at least in regard to this one particular work. My advice is that you take a couple of days off—go fishing, go kayaking, do a jigsaw puzzle—and then go to work on something else.

When you are ready for rewriting, sit down with your door shut (you’ll be opening it to the world soon enough), a pencil in your hand, and a legal pad by your side. Then read your manuscript over.

Make all the notes you want, but concentrate on the mundane housekeeping jobs, like fixing misspellings and picking up inconsistencies. There’ll be plenty; only God gets it right the first time and only a slob says, “Oh well, let it go, that’s what copyeditors are for.”

With six weeks’ worth of recuperation time, you’ll also be able to see any glaring holes in the plot or character development. I’m talking about holes big enough to drive a truck through. It’s amazing how some of these things can elude the writer while he or she is occupied with the daily work of composition.

By the time a book is actually in print, I’ve been over it a dozen times or more, can quote whole passages, and only wish the damned old smelly thing would go away.

Underneath, however, I’m asking myself the Big Questions. The biggest: Is this story coherent?

All novels are really letters aimed at one person. As it happens, I believe this. I think that every novelist has a single ideal reader; that at various points during the composition of a story, the writer is thinking, “I wonder what he/she will think when he/she reads this part?” For me that first reader is my wife, Tabitha.